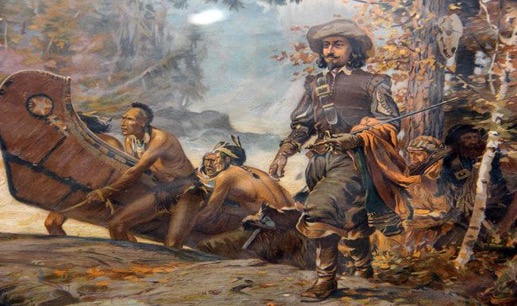

In the early 1600’s, it was the French who were the first Europeans to establish contact with our Algonquin ancestors. They must certainly have been apprehensive and intrigued when they first laid eyes on a Shaginash - White Man.

In 1609, French navigator and explorer Samuel de Champlain took advantage of particular events in Anishinabeg politics that forged a relationship between the Algonquin and French nations that would evolve into a loyal economic and military alliance that would last until 1793.

The Fur Trade

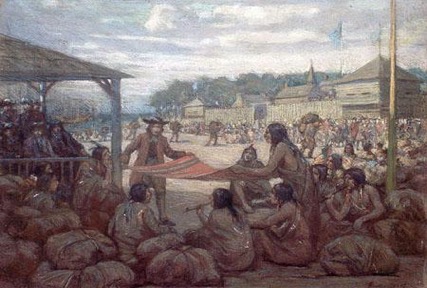

There is no doubt that Europeans quickly assessed the tremendous potential for great profits to be had from this “New World” - the resources seemed virtually limitless. Of particular interest to Europeans, were furs. To exploit this particular resource, Europeans were almost entirely reliant on Native people’s expertise at harvesting furs. In order to do business with our peoples, our Indian customs had to be followed. Only friends could trade. This meant entering into treaties of peace and friendship. The French discerned that the St-Lawrence River and the Kitchisipi (Ottawa River) were key highways to which they needed access in order to exploit the prime fur trapping grounds of the interior. Kitchisipi was located in clearly defined Algonquin territorial boundaries. We guarded our territory zealously and were known to levy tolls to bands who wished to use our waterways. The French knew it was in their interest to secure an alliance with us.

From their base in the St-Lawrence valley, the French made treaties with both our Algonquin ancestors and with the Odawa who lived along the Great Lakes. These treaties allowed the French to project their power throughout the region. For their part, the English tried to offset this development by allying themselves with the Five Nations Iroquois of New York and other groups on the fringes of their new American colonies. The founding of the Hudson's Bay Company in the 1660’s saw the British enter into a new alliance in the North with the James Bay Cree Nations. Until the end of the Seven Years Wars in 1763, these alliances would prove central to the French-British struggle over the Fur Trade, and ultimately for North American superiority.

The Hudson Bay Company (HBC) is the company that built Canada as we know it. This fur trading colossus once controlled nearly 3 million square kilometers of territory with a network of trading posts that reached from the Arctic Ocean to Hawaii, and as far South as San Francisco. The HBC prospered by its shrewdness and deceiving trickery with our peoples. Local Anishinabek describe being asked to stack beaver pelts the height of a rifle in exchange for one.

For the better part of the 1600’s, our upper Ottawa valley ancestors brought their furs down to markets in Montreal and Trois-Rivieres. These long distance ventures were alleviated in the 1670’s when French traders established a post in the Temiscamingue region. The trading post was located on an island at the mouth of the Matabitchuan River, on the West (Ontario) side of Lake Temiscaming, and it was the first trading post on Algonquin lands. But the post’s operations were short-lived. It closed for business in the early 1690’s, supposedly because of attacks by the Five Nations Iroquois. In reality, the Temiscaming trading post was suppressed because of complaints from the Montreal merchants that it was interfering with their profit margins.

In spite of the closure of the Temiscaming trading post, trading in the region gradually centered at Obadjiwan (the ‘narrows’). Just south of present-day Ville-Marie, our people had assembled and traded at Obadjiwan for thousands of years. It was a natural location for the French traders to re-establish a post. They did so in 1717, and called it Fort Temiscamingue. Shortly thereafter, smaller French outposts sprang up throughout the region, including one at the south end of Kipawa Lake and present-day Hunter’s Point.

After the 1760 conquest of New France, Fort Temiscamingue and other outposts in the region were acquired by Anglo-American traders from Montreal. Those operations were purchased in 1794 by the Northwest Company, a competing fur trading business headquartered in Montreal which rivalled the Hudson’s Bay Company with increasing success. In 1821-22 however, the Northwest Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company. A district headquarters was maintained at Fort Temiscamingue until 1902. To ensure its control over the region’s fur stocks, the Hudson’s Bay Company established outposts at Opimika, North of the Long Sault rapids, as well as at the Eastern end of Lake Kipawa. To further stifle competition another post (called Fort Wrath), was set up near the head of Lake Temiscaming in the 1860’s.

In 1847, the Hudson’s Bay Company opened a new outpost on Lake Kipawa called Hunter’s Lodge. It was named after James Hunter, a Scotsman from Orkney Islands, who later moved his post to Hunter’s Point on Ostaboningue Lake. Hunter married a local Algonquin woman. Today, many of his descendants are members of the Timiskaming Eagle Village and Wolf Lake First Nations. Hunter’s Lodge remained in operation until 1902. Today nothing remains of it. The construction of Laniel Dam at the mouth of the Kipawa River in 1911 caused the Lake water level to rise, ultimately submerging the Hunter’s lodge site.

Missionaries

Prior to European contact, our ancestors held strong spiritual beliefs and holistic practices. The Anishinabek worldview promoted harmony with the land and with nature. After the arrival of the French however, our entire manner of interpreting and coexisting with the natural world came under threat. The French brought Roman Catholic missionaries who first introduced our people to Christianity. Their mandate was twofold: to support the efforts of New France and to convert the “savages” to their beliefs. In about 1668, the Jesuit order established a mission of Kentake, or “La Prairie”, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. Later this mission moved to what is now Mohawk Territory at Kahnawake, across from the island of Montreal. By the mid-1670’s, other Iroquois had joined a Sulpician mission that was ministering to convert Hurons and Algonquins. This mission was located at what is now the intersection of Atwater and Sherbrooke Streets at the foot of “La Montagne” or Mount Royal (Kanesatake in Iroquois).

In the late 1600’s, French influence expanded into North America’s interior. French traders and missionaries flooded into the pays d’en haut, or “upper country” (the area between the Ohio valley and the upper Great Lakes), and large trading parties from the interior Nations began making annual summer visits to Montreal via the Great Lakes and the Ottawa or St. Lawrence Rivers for such rites as bible teachings, baptisms, and marriages. By 1673, Jesuit missions were established at Sault Ste-Marie and Michilimackinac. In 1717, the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice was granted land on the North Shore of the Lake of Two Mountains in an effort to move their missions away from the negative influence of the French settlers. By 1721, 150 Iroquois, Huron, and Algonquin had persuaded to move their families to a new mission. Those living at Sault-au-Recollet, as well as the Algonquins from Ste-Anne-du-bout-de-L’isle relocated to the new mission where Algonquins formed one village, and the Iroquois and Hurons another. The Iroquois dubbed the new mission, Kanesatake (the mountain), in memory of the original mission of Montreal Island.

We can speculate as to the reasoning behind our ancestors’ increasing interest in converting to the Roman Catholic faith. But in all likelihood, it was probably to accommodate the burgeoning inter-racial marriages between the Whites and the Indians which in turn fostered better trade relations and military alliances, effectively drawing the two cultures closer together. Nonetheless, the adoption of the Roman Catholic faith drastically disrupted millennia-old spiritual practices and beliefs, and it would have profound cultural consequences for many of our people and continue today.